Monday, October 15, 2007

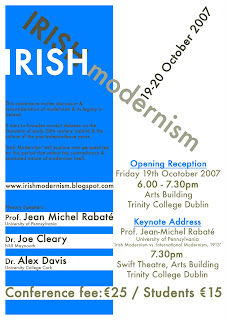

Irish Modernism Conference Programme

Irish Modernism Conference Programme

Arts Building

Trinity College Dublin, 19-21 October 2007

Friday, 19th October

16:00 – 17:30 Conference Registration

(outside Swift Theatre, Arts Building)

18.00-19.30 Wine Reception

19:30 – 20:30 OPENING ADDRESS (Swift Theatre)

Prof. Jean-Michel Rabaté, University of Pennsylvania

‘Irish Modernism vs. International Modernism, 1913’

Chair: Dr Sam Slote, Trinity College Dublin

Saturday, 20th October

9:00 – 10:00 KEYNOTE ADDRESS (Swift Theatre)

Dr Joe Cleary, NUI Maynooth

‘Modernism After Modernism: Reconfiguring the Trinity’

Chair: Prof. Nicholas Grene, Trinity College Dublin

10:00-11:30 PANEL SESSION I

The Politics of Time: Irish Modernist Temporalities (Swift Theatre)

John Waters (NYC), 'Theorizing Irish Counter-Modernism: Realism, Genre, and Progressive temporality in Irish fiction, 1920-1923'

Gregory Dobbins (University of California, Davis), ‘Work-time, Leisure-time, Story-time and Irish Time’

Lionel Pilkington (NUI Galway), 'Modernity and Moving Statues: Ireland, 1985'

Chair: Dr Carol Taaffe, Beijing Foreign Studies University

James Joyce and Irish Modernism (Rm 3071)

Sam Slote (TCD), ‘Garryowen and the Bloody Mangy Mongrel of Irish Modernity’

Margot Backus (NUI Galway), ‘“The Cracked Lookingglass of a Servant”: Scandal as Cultural Strategy in Ulysses.’

Eugene O’Brien (MIC Limerick), ‘ “He Had Read Her out a Ghost Story”: Hauntological Identifications between James Joyce’s ‘Eveline’ and Claire Keegan’s ‘The Parting Gift’’

Chair: Prof. Anne Fogarty, University College Dublin

Memory and Destiny: The Shape of Irish Modernity (Rm 4050A)

Jim Shanahan (TCD), ‘Frank Mathew’s The Wood of the Brambles (1896): A Forgotten Irish Modernist Novel’

Eimear O’Connor (UCD), 'Modernity and Realism: Sean Keating and The Playboy of the Western World'

John Borgonovo (UCC), ‘Dawn, Nation, and Destiny: Irish Cinema and the War of Independence’

Stanley Van Der Ziel (UCD), ‘John McGahern’s The Leavetaking’

Chair: Dr Angelina Lynch, University College Dublin

11.30-11.45 Coffee Break

11:45 - 13:15 PANEL SESSION II

Scholars and Shopgirls: The Reception of Modernism (Rm 3071)

Lisa Fluet (Boston College), ‘James Joyce, Scholarship Boys and British Cultural Studies’

John Nash (Durham University), ‘Irish Modernism? The Reception of Joyce in Ireland, 1915-1930’

Jenny McDonnell (TCD), ‘ “The Brassy Little Shopgirl”: Frank O’Connor and the Legacy of Katherine Mansfield’

Chair: Prof. Paige Reynolds, College of the Holy Cross

Ireland and Europe (Swift Theatre)

Robert Baines (TCD), ‘Seeing through the Mask: Valery Larbaud’s ‘James Joyce’ and the Problem of Irish Modernism’

Seán Kennedy (St.Mary’s University), ‘Ireland/ Europe… Beckett/ Beckett’

Peter Fifield (University of York), ‘ “Art has nothing to do with clarity”: Samuel Beckett and the Language of Visual Aesthetics’

Chair: Prof. James Wilson, East Carolina University

Modernism, Revolution and Popular Culture (Rm 4050A)

Deaglán Ó Donghaile (NUI Maynooth), ‘Liam O’Flaherty and the Irish Revolutionary Bohemia’

Eamonn Hughes (Queen’s University Belfast), ‘Flann O’Brien, Modernism and Popular Culture’

Steve Coleman (NUI Maynooth), ‘Modernism and Vernacular Culture: Maude, Ó Cadhain, Ó Conaire, Ó Riada’

Chair: Dr. Carol Taaffe, Beijing Foreign Studies University

13.15-14.30Lunch Break

14:30 – 15:30 KEYNOTE ADDRESS (Swift Theatre)

Dr Alex Davis, University College Cork

‘Irish Modernisms and the Modern Movement’

Chair: Mr Gerald Dawe, Trinity College Dublin

15:30 – 17:15 PANEL SESSION III

Modernism and the Catholic Intellectual (Swift Theatre)

Benjamin Keatinge (SEEU), ‘Coffey, Devlin, MacGreevy and the Poetry of Prayer’

Rhiannon Moss (Queen Mary, London), ‘Thomas MacGreevy, Catholicism and Modernism in 1930s Ireland’

James Matthew Wilson (East Carolina University), ‘“Ireland’s Eliot?”: Late Modernism, Mysticism and the Marketplace in Denis Devlin’s The Heavenly Foreigner’

Jennika Baines (UCD), ‘A Rock and a Hard Place: Sweeny’s Role as Sisyphus and Job in At Swim-Two-Birds’

Chair: Dr Karen Brown, University College Dublin

Sinning Against the State: Rewriting Irish Cultural History (Rm 4050A)

Shillana Sanchez (Arizona State University), ‘Of Mimicry and Mockery: Flann O'Brien Relates the Nation'

Eibhlín Evans (UCD), ‘'a lacuna in the palimpsest': A Reading of Flann O'Brien's At Swim-Two Birds’

Kathy D'Arcy (UCC), 'Experiment in Error: Irish Women Poets Engaging with Modernism in the 1930s, 40s and 50s'

Chair: Dr. Eammon Hughes, Queens University Belfast

Irish Modernism and the Literary Revival (Rm 3071)

Julia Whittredge (UCC), ‘Modern, Modernising, Modernism: Revisiting the Poetry of the Irish Literary Revival’

Wit Pietrzak (University of Lodz), ‘Predefining Modernism: W.B.Yeats and Symbolic Ontology’

Anne Markey (TCD), ‘Modernism, Maunsel and the Irish Short Story’

Chair: Prof. Lisa Fluet, Boston College

17.15-17.30 Coffee Break

17:30 – 18:30 ROUNDTABLE SESSION (Swift Theatre)

Chair: Dr Sam Slote, Trinity College Dublin

Participants:

Prof. Anne Fogarty, University College Dublin

Dr John Nash, Durham University

Dr. Derek Hand, St Patrick's College, DCU

Dr Eve Patten, Trinity College Dublin

21.00 CONFERENCE DINNER

Eliza Blues Restaurant, Wellington Quay

SUNDAY, 21st OCTOBER

10.00 – 11:30 PANEL SESSION 4

The Irish Avant-Garde: Surreal Landscapes (Rm 3071)

Karen E. Brown (UCD), ‘Thomas MacGreevy and Irish Modernism: Between Word and Image’

Jaki McCarrick (NUI Maynooth), ‘The Great Hunger: An Apocalypse of Irish Modernism and Surrealism’

Caitríona Ryan (Swansea University), ‘The Poetics of Tom MacIntyre’

Chair: Dr Eibhlin Evans, University College Dublin

Experimentalism and Irish Theatre (Swift Theatre)

Dathalinn O’Dea (Boston College), ‘Staging the Nation: W.B.Yeats and Theatre as the Third Space’

Michael McAteer (Queen’s University Belfast), ‘German Expressionism and Irish Drama: Yeats, O’Casey and McGuinness’

Maeve Tynan, (MIC Limerick) ‘ “Let us not speak”: Language and the Diminishing Self for Beckett’s Women’

Chair: Dr Carol Taaffe, Beijing Foreign Studies University

11.30-11.45 Coffee Break

11:45 – 13:15 PANEL SESSION 5

New Languages: Modernism and the Visual Arts (Swift Theatre)

Róisín Kennedy (National Gallery of Ireland), ‘The White Stag Group – Experimentalism or Mere Chaos?’

Elaine Sissons (IADT), ‘Look Behind You!: Experimental Theatre and Design in Ireland 1918-1932’

Bernadette McCarthy (UCC), ‘Painting Stories, Telling Pictures: W. B. Yeats and Word Image Ideologies’

Chair: Dr. MIchael McAteer, Queens University Belfast

Building Modern Ireland: Architecture, Media and Transport (Rm 3071)

Paige Reynolds (College of the Holy Cross), ‘Colleen Modernism: Media and Materiality in Twentieth-Century Irish Women’s Writing’

Edwina Keown (St Pats, DCU), 'Shannon Airport, 1950s modernity and a late modernist romance of the West in Elizabeth Bowen's A World of Love (1955)’

Ellen Rowley (TCD), ‘Dublin Architecture 1945-1960: The Case of Catholic Church Design’

Chair: Prof. Gregory Dobbins, University of California, Davis

13:30 – 14:00 CLOSING REMARKS (Swift Theatre)

Sunday, September 9, 2007

List of Abstracts

Professor Margot Backus, NUI Galway

“The Cracked Lookingglass of a Servant”: Scandal as Cultural Strategy in Ulysses.

“The Cracked Lookingglass of a Servant”: Scandal as Cultural Strategy in Ulysses.

As an Irish Catholic educated within the second-tier university system that served throughout the United Kingdom, as Terry Eagleton famously argues, both to disguise and institutionalize growing cleavages between the Oxbridge elite, a philistine middle class and an alienated working class shot through with ethnic and regional grievances, James Joyce, as an intellectually and formally-ambitious author, occupied an inherently compromised position within existing Irish and the British cultural hierarchies. Attempts on his part to emulate the tastefully erudite allusions of his highbrow modernist betters would have left him open to accusations of imperfect mimicry, or, symbolically, of the “plagiarism” of which Bloom, in “Circe,” stands accused by his class superior, Philip Beaufoy. On the other hand, the deliberate, overt violations of prevailing decorum for which he increasingly opted inevitably exposed him to charges of ill-bred intellectual ostentation and tastelessness. Symbolically, owing to his lack of proper university credentials (like Bloom, Joyce could be said to have learned much of his art from the “university of life”), Joyce was vulnerable to accusations that he had simply smeared shit on his pages, as Bloom is accused of doing in a sensational courtroom moment that equates Bloom’s shameful but also natural and unavoidable crime with the crimes of Oscar Wilde, which were, like Bloom’s, confirmed in court through the sensational display of shit-marked sheets. Thus, this excruciatingly shameful moment of revelation in “Circe” significantly merges the inescapable shame of Joyce’s class and ethnic inferiority with the ritually-imposed shame of Wilde’s sexual and intellectual irregularities.

As Joyce foresees, in “Circe” and elsewhere, charges of shameful shit-smearing were indeed leveled at him by British highbrow modernists such as Virginia Woolf, and by the Dublin intelligentsia in the person of Trinity’s Provost, John Pentland Mahaffy. Mahaffy called attention to Joyce’s shameful class and educational origins by describing his work as exemplifying the ill effects of educating the “island’s aborigines,” and identified Joyce’s literary efforts with unclean incontinence as well as immaturity when he identified Joyce with the “corner boys who spit into the Liffey.” By citing a range of famous and influential scandals, most particularly the Parnell and Wilde scandals, along with the older heresies that form the earliest origins of the term scandal, and insisting on his own work’s analogy to these earlier scandals, Joyce sought to make clear that he was not neither imperfectly emulating his betters nor ignorantly violating the established rules of literary decorum, but rather that both his emulations and violations were deliberate. Through a stylistics of scandal, Joyce was able to strategically make his work less vulnerable, in the long-term, at least, to arguments either that it was purely derivative, or that it was simply nonsense, the two charges to which Joyce’s subject position made his work most vulnerable.

Jennika Baines, University College Dublin

A Rock and a Hard Place: Sweeny’s Role as Sisyphus and Job in At Swim-Two-Birds

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus writes that man’s existence is a hopeless, purposeless struggle. He argues that the man conscious of this absurd situation must be able to function within and against this hopelessness. He uses as his absurd ideal the mythical Sisyphus, doomed by the gods to forever roll a rock up a mountain.

At the centre of Flann O’Brien’s modernist masterpiece At Swim-Two-Birds is the perpetually suffering mad King Sweeny. Banished to a life of pain and loneliness, Sweeny is nevertheless put forward as the one true creator in this novel of novels. Sween’s lays centre around his experiences in the natural world. This authenticity is unlike any other writer, story-teller or character conjurer who appears.

But while Sweeny and Sisyphus share perpetual punishment, the key difference between these two characters is that Camus insists that the world of the absurd hero must necessarily be a godless one, for God’s existence necessarily provides an ultimate reason. In O’Brien’s work God wants Sweeny to suffer – and suffer horribly. It is therefore significant to the understanding of O’Brien’s portrayal of the absurd that we consider not just Sisyphus, but also Job.

Both O’Brien and the author of the Book of Job express the absurd through the conditions of a deep faith in God. This is a suffering life existing beneath the pressure of an overwhelming incapacity to understand. And yet, there are possibilities of authentic artistic expression despite, and perhaps in revolt against, their suffering. In this way, At Swim-Two-Birds exemplifies the concerns of the modernist writer.

Robert Baines, Trinity College Dublin

Seeing through the Mask: Valery Larbaud’s ‘James Joyce’ and the Problem of Irish Modernism

On December 7, 1921 in the Maison des Amis des Livres in Paris the respected critic Valery Larbaud gave a talk on one of the twentieth century’s great literary constructs and his new novel. Aided, perhaps even guided, by his subject, Larbaud presented a rich, personal portrait of Joyce’s works and achievements, culminating in his hugely influential reading of Ulysses. Having been given access to the drafts and the schema, Larbaud was able to suggest how one might move beyond the basic narrative and so transform this, to use his phrase, ‘brilliant but confused mass’ into something more deliberate and complex. This talk enabled a Ulysses that was cosmopolitan and modernist rather than local and naturalistic. Larbaud did not simply help to define ‘the French Joyce’, he made him necessary. In asserting that, with Joyce, Ireland was making a ‘sensational re-entrance into high European Literature’, Larbaud offended a number of Irish critics. They responded to this perceived denigration by attempting to reject his reading and to reclaim the Irishman as one of their own. A significant division was created. In this paper, I want to present a detailed reading of Larbaud’s famous talk and to show how, intentionally and unintentionally; it created such disparate readings of the same text. I will consider whether Larbaud actually created this division or whether the Irish modernist he spoke of forced Ireland and modernism apart. Finally, I intend to examine how one might begin to reconcile these seemingly antagonistic concepts.

Johnny Borg, University College Cork

Dawn, Nation, and Destiny: Irish Cinema and the War of Independence

During the past 80 years, the Irish Independence struggle of 1919-1921 has been depicted in countless films. Most of these productions were created by non-Irish artists for overseas audiences, or released long after the conflict ceased to be a living memory in Ireland. However, three Irish productions were made within fifteen years of the Anglo-Irish War’s conclusion. My paper will examine those three forgotten films and determine how post-revolution Irish cinema portrayed the War of Independence.

The three Irish-made films are: “Irish Destiny” (1926), “Guests of the Nation (1935), and “The Dawn” (1936.) Each movie offers tangible connections to the independence struggle, with screenwriters, actors, and crews bringing their own recent revolutionary experiences to the filmmaking process. The productions provide an intriguing glimpse of the Irish mindset in the fifteen years after the conflict. Cinematic themes matured as time elapsed between the productions and the Revolution. The simplistic propaganda of “Irish Destiny” gave way to the moral questioning in “Guests of the Nation” and the probing realism of “The Dawn.” None of the films, though, challenged the Irish Republican’s physical force ideology, and all celebrated the independence struggle. Likewise, each screenplay depicted clear national unity and a strong resentment of British conduct against Irish civilians.

By highlighting the films’ common themes and stark differences, I will explore the indigenous cinematic perceptions of the Irish Revolution. My paper will show how Irish filmmakers interpreted their country’s War of Independence, and how that interpretation evolved over the ensuing 15 years.

John Borgonovo (MA History, UCC) is a PhD student in the University College Cork History Department. He is the author of Spies, Informers, and the “Anti-Sinn Fein Society”: The Intelligence War in Cork City 1920-1921, and the editor of Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence (both published in 2006 by Irish Academic Press.) He also produced ‘City of Baseball: A Story of the American Game in Italy’, a feature-length documentary currently showing in film festivals in the United States.

Dr Karen E. Brown, University College Dublin

‘Thomas MacGreevy and Irish Modernism: Between Word and Image’

Modern Irish writing – an extraordinary thing in a mainly Catholic country – is almost entirely devoid of a visual sense. And yet the greatest writing has always owed a great deal to painting, as the greatest painting owes a great deal to literature.

(Thomas MacGreevy, 1927)

Thomas MacGreevy is perhaps best remembered as a friend and confidant of many leading literary and artistic figures in the early twentieth-century Ireland, including Jack Yeats, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. But he also published a vast amount of criticism on the arts in Ireland, London and France, and published poetry in response to his experiences in the Great War, events in Ireland after the Easter Rising, and the visual arts. This paper focuses specifically on MacGreevy’s poetic responses to the visual arts, and considers how references to painters, paintings and architecture inform and shape his work on both syntactic and semantic levels. I argue that MacGreevy’s poetry is best described as ‘transitional’, as it links Irish cultural nationalism with experiments associated with international modernism. For example, while Samuel Beckett praises Jack Yeats as the ‘modern’ Irish painter, MacGreevy challenges this view by pointing out the ‘national’ aspects of the paintings. It seems a paradox therefore that in his poetry after Jack Yeats’s paintings MacGreevy then adopts a soi-dissant modernist idiom. By presenting close readings of selected poems and new material from his Archive in Trinity College, this paper shows that MacGreevy broke down distinctions between ‘the national’ and ‘the modern’ in his pictorialist poetics.

Dr. Steve Coleman, Department of Anthropology, National University of Ireland

Modernism and vernacular culture: Maude, Ó Cadhain, Ó Conaire, Ó Riada.

This paper addresses the continuities between the Irish-language culture of the post-Famine Gaeltacht and the modernist work of Máirtín Ó Cadhain, Pádraig Ó Conaire, Caitlín Maude, and Seán Ó Riada. Each in their own way worked against the contradictions imposed by modernist ideology and practice. I argue that modernisms are metacultural processes which work to deny agency and reflexivity to other elements of culture, which they thereby reconstruct as ‘tradition’. Modernist texts deploy systems of chronotopes in which they appear to rescue, redeem and transcend the 'non-modern'. This creates intense conflicts when modernist authors (composers, etc.) identify with and seek to build upon reflexive, dynamic elements within 'tradition' which resist this process. By taking “tradition” itself as metacultural, they construct new ‘hybrids’ which challenge national and international modernisms on a formal level. I examine the work of Ó Cadhain, Ó Conaire, Maude and Ó Riada and their reception for traces of these formal conflicts involving the semiotic ideologies of linguistic, generic and musical form.

As Joyce foresees, in “Circe” and elsewhere, charges of shameful shit-smearing were indeed leveled at him by British highbrow modernists such as Virginia Woolf, and by the Dublin intelligentsia in the person of Trinity’s Provost, John Pentland Mahaffy. Mahaffy called attention to Joyce’s shameful class and educational origins by describing his work as exemplifying the ill effects of educating the “island’s aborigines,” and identified Joyce’s literary efforts with unclean incontinence as well as immaturity when he identified Joyce with the “corner boys who spit into the Liffey.” By citing a range of famous and influential scandals, most particularly the Parnell and Wilde scandals, along with the older heresies that form the earliest origins of the term scandal, and insisting on his own work’s analogy to these earlier scandals, Joyce sought to make clear that he was not neither imperfectly emulating his betters nor ignorantly violating the established rules of literary decorum, but rather that both his emulations and violations were deliberate. Through a stylistics of scandal, Joyce was able to strategically make his work less vulnerable, in the long-term, at least, to arguments either that it was purely derivative, or that it was simply nonsense, the two charges to which Joyce’s subject position made his work most vulnerable.

Jennika Baines, University College Dublin

A Rock and a Hard Place: Sweeny’s Role as Sisyphus and Job in At Swim-Two-Birds

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus writes that man’s existence is a hopeless, purposeless struggle. He argues that the man conscious of this absurd situation must be able to function within and against this hopelessness. He uses as his absurd ideal the mythical Sisyphus, doomed by the gods to forever roll a rock up a mountain.

At the centre of Flann O’Brien’s modernist masterpiece At Swim-Two-Birds is the perpetually suffering mad King Sweeny. Banished to a life of pain and loneliness, Sweeny is nevertheless put forward as the one true creator in this novel of novels. Sween’s lays centre around his experiences in the natural world. This authenticity is unlike any other writer, story-teller or character conjurer who appears.

But while Sweeny and Sisyphus share perpetual punishment, the key difference between these two characters is that Camus insists that the world of the absurd hero must necessarily be a godless one, for God’s existence necessarily provides an ultimate reason. In O’Brien’s work God wants Sweeny to suffer – and suffer horribly. It is therefore significant to the understanding of O’Brien’s portrayal of the absurd that we consider not just Sisyphus, but also Job.

Both O’Brien and the author of the Book of Job express the absurd through the conditions of a deep faith in God. This is a suffering life existing beneath the pressure of an overwhelming incapacity to understand. And yet, there are possibilities of authentic artistic expression despite, and perhaps in revolt against, their suffering. In this way, At Swim-Two-Birds exemplifies the concerns of the modernist writer.

Robert Baines, Trinity College Dublin

Seeing through the Mask: Valery Larbaud’s ‘James Joyce’ and the Problem of Irish Modernism

On December 7, 1921 in the Maison des Amis des Livres in Paris the respected critic Valery Larbaud gave a talk on one of the twentieth century’s great literary constructs and his new novel. Aided, perhaps even guided, by his subject, Larbaud presented a rich, personal portrait of Joyce’s works and achievements, culminating in his hugely influential reading of Ulysses. Having been given access to the drafts and the schema, Larbaud was able to suggest how one might move beyond the basic narrative and so transform this, to use his phrase, ‘brilliant but confused mass’ into something more deliberate and complex. This talk enabled a Ulysses that was cosmopolitan and modernist rather than local and naturalistic. Larbaud did not simply help to define ‘the French Joyce’, he made him necessary. In asserting that, with Joyce, Ireland was making a ‘sensational re-entrance into high European Literature’, Larbaud offended a number of Irish critics. They responded to this perceived denigration by attempting to reject his reading and to reclaim the Irishman as one of their own. A significant division was created. In this paper, I want to present a detailed reading of Larbaud’s famous talk and to show how, intentionally and unintentionally; it created such disparate readings of the same text. I will consider whether Larbaud actually created this division or whether the Irish modernist he spoke of forced Ireland and modernism apart. Finally, I intend to examine how one might begin to reconcile these seemingly antagonistic concepts.

Johnny Borg, University College Cork

Dawn, Nation, and Destiny: Irish Cinema and the War of Independence

During the past 80 years, the Irish Independence struggle of 1919-1921 has been depicted in countless films. Most of these productions were created by non-Irish artists for overseas audiences, or released long after the conflict ceased to be a living memory in Ireland. However, three Irish productions were made within fifteen years of the Anglo-Irish War’s conclusion. My paper will examine those three forgotten films and determine how post-revolution Irish cinema portrayed the War of Independence.

The three Irish-made films are: “Irish Destiny” (1926), “Guests of the Nation (1935), and “The Dawn” (1936.) Each movie offers tangible connections to the independence struggle, with screenwriters, actors, and crews bringing their own recent revolutionary experiences to the filmmaking process. The productions provide an intriguing glimpse of the Irish mindset in the fifteen years after the conflict. Cinematic themes matured as time elapsed between the productions and the Revolution. The simplistic propaganda of “Irish Destiny” gave way to the moral questioning in “Guests of the Nation” and the probing realism of “The Dawn.” None of the films, though, challenged the Irish Republican’s physical force ideology, and all celebrated the independence struggle. Likewise, each screenplay depicted clear national unity and a strong resentment of British conduct against Irish civilians.

By highlighting the films’ common themes and stark differences, I will explore the indigenous cinematic perceptions of the Irish Revolution. My paper will show how Irish filmmakers interpreted their country’s War of Independence, and how that interpretation evolved over the ensuing 15 years.

John Borgonovo (MA History, UCC) is a PhD student in the University College Cork History Department. He is the author of Spies, Informers, and the “Anti-Sinn Fein Society”: The Intelligence War in Cork City 1920-1921, and the editor of Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence (both published in 2006 by Irish Academic Press.) He also produced ‘City of Baseball: A Story of the American Game in Italy’, a feature-length documentary currently showing in film festivals in the United States.

Dr Karen E. Brown, University College Dublin

‘Thomas MacGreevy and Irish Modernism: Between Word and Image’

Modern Irish writing – an extraordinary thing in a mainly Catholic country – is almost entirely devoid of a visual sense. And yet the greatest writing has always owed a great deal to painting, as the greatest painting owes a great deal to literature.

(Thomas MacGreevy, 1927)

Thomas MacGreevy is perhaps best remembered as a friend and confidant of many leading literary and artistic figures in the early twentieth-century Ireland, including Jack Yeats, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. But he also published a vast amount of criticism on the arts in Ireland, London and France, and published poetry in response to his experiences in the Great War, events in Ireland after the Easter Rising, and the visual arts. This paper focuses specifically on MacGreevy’s poetic responses to the visual arts, and considers how references to painters, paintings and architecture inform and shape his work on both syntactic and semantic levels. I argue that MacGreevy’s poetry is best described as ‘transitional’, as it links Irish cultural nationalism with experiments associated with international modernism. For example, while Samuel Beckett praises Jack Yeats as the ‘modern’ Irish painter, MacGreevy challenges this view by pointing out the ‘national’ aspects of the paintings. It seems a paradox therefore that in his poetry after Jack Yeats’s paintings MacGreevy then adopts a soi-dissant modernist idiom. By presenting close readings of selected poems and new material from his Archive in Trinity College, this paper shows that MacGreevy broke down distinctions between ‘the national’ and ‘the modern’ in his pictorialist poetics.

Dr. Steve Coleman, Department of Anthropology, National University of Ireland

Modernism and vernacular culture: Maude, Ó Cadhain, Ó Conaire, Ó Riada.

This paper addresses the continuities between the Irish-language culture of the post-Famine Gaeltacht and the modernist work of Máirtín Ó Cadhain, Pádraig Ó Conaire, Caitlín Maude, and Seán Ó Riada. Each in their own way worked against the contradictions imposed by modernist ideology and practice. I argue that modernisms are metacultural processes which work to deny agency and reflexivity to other elements of culture, which they thereby reconstruct as ‘tradition’. Modernist texts deploy systems of chronotopes in which they appear to rescue, redeem and transcend the 'non-modern'. This creates intense conflicts when modernist authors (composers, etc.) identify with and seek to build upon reflexive, dynamic elements within 'tradition' which resist this process. By taking “tradition” itself as metacultural, they construct new ‘hybrids’ which challenge national and international modernisms on a formal level. I examine the work of Ó Cadhain, Ó Conaire, Maude and Ó Riada and their reception for traces of these formal conflicts involving the semiotic ideologies of linguistic, generic and musical form.

Kathy D’Arcy, University College Cork

Experiment in Error: Irish Women Poets Engaging with Modernism in the 1930s, 40s and 50s:

In an essay on the Irish modernist poet Thomas MacGreevy, J. C. C.

Mays writes that “MacGreevy has a special place in the Irish tradition, because he was a modernist, but he was a special kind of modernist because he was Irish.” An essay in the same collection, by Anne Fogarty, mentions the “almost forgotten names” of some Irish women poets writing around the same time as MacGreevy, noting that, while the special situation of Irish male modernist poets often consigned them to an obscurity from which their work is only recently being recovered, their female colleagues’ work has endured an even greater degree of segregation from the accepted literary canon. “To triumphantly reinstate their work by seeing it as part of a diffuse but coherent literary context which embraces male and female writing alike,” states Fogarty, “would involve a self-blinkering and premature denial of the unremittingly androcentric and fragmented nature of the Irish modernist literary scene.”

This paper will explore the work of those of MacGreevy’s contemporaries whose careers have been filtered through that other layer of “specialness” – their gender. As Mays points out, falling between two (or three) stools can catalyse the production of more original and challenging work, and Irish women poets who became excluded from the dominant nationalist tradition and grappled with the (arguably similarly exclusive) innovations of European modernism could bring their difference to bear on the emerging themes and forms which they encountered. The beautiful, highly innovative poetry which resulted can, I believe, no longer be discounted by scholars of Irish modernist literature.

Dr Eibhlín Evans, University College Dublin

"'a lacuna in the palimpsest'; A Reading of Flann O'Brien's At Swim Two Birds."

This paper will offer a reading of Flann O’ Brien’s novel, At Swim Two Birds (1939) as an insightful and innovative engagement with issues of Irish identity and Irish literary culture. Literary criticism has celebrated O’Brien’s novel, applauding its comic inclinations, its deconstructionist strategies, its post-structural affinities, its anarchic tendencies, its multi-generic inclusions and its Joycean range of literary styles and voices. However, none of these critiques give a satisfactory explanation for the structural originality of the text nor do they explain the exclusively Irish orbit of O’Brien’s novel.

This reading of At Swim Two Birds identifies it as ‘a lacuna in the palimpsest’ of Irish identity formation in which the author’s anarchic tendencies are central to his assault on a particular ideology, on the literary vehicles employed in its promotion, and the impact on Irish writing that such a situation produced. I will argue that this novel can be read as a disruptive intervention in the layering of literary proscriptions for Irish identities which preceded its publication in 1939. O’Brien’s literary strategies can be understood as deliberate attempts to escape the strait-jacket of an identity model contained within a range of nationalistic narratives, employed and promoted as desirable in Ireland for half a century.

We can recognize this novel as a literary challenge to a particular cultural agenda where O’Brien’s literary strategies and his varied inclusions combine in a sophisticated assault on the real repressions, and the often comic absurdities, involved in a particular situation, that is, the repressive cultural nationalism of Ireland in the 1930’s and its impact on Irish writing and on Irish identity. O’ Brien’s novel takes the prevailing narrative models and, through their playful juxtaposition, he offers a serious critique of the limiting and confining imperatives behind their endorsement and their employment.

Professor Lisa Fluet, Boston College

James Joyce, Scholarship Boys and British Cultural Studies

This paper presents the beginnings of a reception-history of Joyce’s major works, within the context of the literary histories of literature in English emerging through British cultural studies. Focusing principally on the critical work of H. G. Wells, George Orwell, Raymond Williams, Richard Hoggart, and Paul Gilroy, I am interested in developing an account of the return to a postimperial “English” culture exemplified by the turn to cultural studies in the postwar period, and anticipated in the early critical work of Wells and Orwell. Following Jed Esty’s recent study A Shrinking Island, this paper traces the development of “James Joyce” as a disciplinary object for literary criticism, and the various ways in which Joyce has been deployed as an exemplum of cosmopolitan, anti-nationalist modernism (Moretti and others), as well as an exemplum of a nationally-specific Irish modernism (Nolan, Duffy) and “semicoloniality” (Howes, Attridge). Joyce as a subject for British cultural studies has posed some interesting difficulties: Williams’ Leavisite tendencies, for example, and the ways that cultural studies came to be interwoven with British political life and the New Left in the post-war period, have led to a de-emphasis of Joyce within cultural studies’ histories of the specifically English novel. This situation leads me to Paul Gilroy’s work, specifically, and the ways in which he has analyzed the collusion between British cultural studies and keeping the “black out of the union jack.” At the same time, this paper focuses on the fate of a social type identified in Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy—the “scholarship boy”—within Joyce’s works. Taking up Stephen Hero (1904), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), and Ulysses (1922), I reconceive Stephen Dedalus’ difficulties in maintaining social poise in terms of literary modernism’s ambiguous novelistic relations with the figure of the awkward, earnest and anxious “scholarship boy.” Working backwards from Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy (1957), where the scholarship boy’s difficulties with sociability were first most famously treated, I analyze the complications posed to Hoggart’s study—and to its post-war participation in defining both culture and society as objects of study—by the figure of the modernist, Irish scholarship boy.

Dr Eamonn Hughes, Queens University Belfast

Flann O’Brien, Modernism and Popular Culture

Considerations of Flann O’Brien’s status as modernist or post-modernist writer, as of his relationship to James Joyce’s work, have focused to a large extent on the formal and ludic aspects of his writing. Remembering that O’Brien was part of a student generation in the 1930s ‘equally concerned’ as his contemporary Niall Sheridan put it, ‘about the cultural identity of the new State and its place in the wider intellectual context of Europe…’ enables us to think about the ways in which his texts, particularly At Swim-Two-Birds and the ‘Cruiskeen Lawn’ column, engage with European aesthetic and cultural debates, particularly in regard to ideas about tradition and, in turn, about the ownership and control of culture. By reference to two key essays on tradition and history - T. S. Eliot’s ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ (1919) and Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936) - this paper will make the case that O’Brien’s writing constructs an idea of tradition which is more accommodating of popular culture than either High Modernism, arguably constructed as a bulwark against the burgeoning of mass culture, or the Irish Free State which was still anxious about how such matters should be evaluated and policed.

Dr Benjamin Keatinge, South Eastern European University, Macedonia

Coffey, Devlin, MacGreevy and the Poetry of Prayer

“All poetry” wrote Samuel Beckett in his 1934 review of Thomas MacGreevy’s Poems “is prayer”. This insight might serve as a unifying principle underscoring the Catholic modernism of Coffey, Devlin and MacGreevy. Whether it be Devlin’s overt religiosity in such poems as ‘Est Prodest’ and ‘The Heavenly Foreigner’, or MacGreevy’s “humanistic quietism”, or Coffey’s meditative questing in such poems as Advent and ‘The Prayers’, all these poets use prayer, and intercession, as part of the method, rhetoric and content of their poems. J.C.C. Mays describes Brian Coffey’s poetry as a “poetry of intention”, rather than revelation and fulfilment and it is this aspirational quality which unifies these poets’ work. They are, in Beckett’s words, waiting “for the thing to happen” and it is implied that “the meaning is in the waiting” (R.S. Thomas, ‘Kneeling’). This paper explores the solipsistic and communicative function of prayer in these poets’ work finding that their “pure winged linking” (‘Est Prodest’) involves, in Brian Coffey’s terms “acts of recognition of an adult humility based on hope.” These Catholic aesthetics both overlap with and resist the nationalistic pieties of 1930s Ireland in a complex relationship with Irish social reality which this paper also addresses.

Dr Róisín Kennedy National Gallery of Ireland

The White Stag Group – Experimentalism or Mere Chaos?

The cultural isolation of the war years had a dramatic impact on the exhibition of contemporary visual art in Dublin. The period saw growing public awareness of modernist art. This increased interest was partly the result of an influx of foreign artists into Dublin, the most significant of which was the White Stag Group. Founded in London in 1935 by Basil Rákóczi and Kenneth Hall, the group reformed itself in Dublin in 1940. Other artists gravitated towards the group, and participated in its exhibitions, held between April 1940 and October 1945.

This paper will examine the critical debate on modernist art in Ireland generated by the exhibitions and associated publications of the White Stag Group. These presented Irish critics with a number of difficulties. The theoretical underpinning of its art practice was new to an Irish audience, who were unaccustomed to art which claimed to be solely concerned with personal expression. As a result the White Stag prompted a more complex critical response than that found in relation to other manifestations of modernism in Irish visual art. The cosmopolitan approach of the White Stag challenged conventional expectations of art as reflective of communal and, by extension, national principles. This paper will examine how the self-promotion and determination to connect its work to the international art world made the White Stag an important precedent for later developments in Irish visual art.

Dr Sean Kennedy, St Mary’s University, Halifax

Ireland/Europe…Beckett/Beckett

This paper will explore ways in which a more nuanced account of Irish modernism can resolve a recurrent tension in Beckett Studies between two entities, ‘the Irish Beckett’ and ‘Beckett the European’. Often, there is an implicit either/or logic that structures debates about Beckett’s Irishness, suggesting that Irishness and modernism are somehow mutually exclusive categories of experience, so that Beckett only truly becomes modernist when Ireland ‘disappears’ from his work after 1946. Tracing the persistence of that binary in the critical work of Vivian Mercier, Richard Kearney and, more recently, Stan Gontarski and Chris Ackerley’s Grove Companion to Samuel Beckett (2004), I want to challenge the notion of Ireland as an impediment to modernist experimentation, and explore ways in which Irishness has, in fact, been an extraordinarily fertile source of modernists sensibilities, paying particular attention to Beckett’s post-war work. In a close reading of Gontarski and Ackerley’s introduction, and drawing on recent theoretical work by Terence Brown, Joe Cleary, Adrian Frazier and others, this paper will suggest the need for a re-evaluation of Ireland’s relationship to modernism and, by the same token, of Samuel Beckett’s relationship to both. The aim is to deconstruct the Ireland/Europe binary and refute certain too-easy assumptions about Ireland’s status as a place and mentalité to be escaped in the quest for artistic freedom.

Dr Edwina Keown, St Patrick's College, DCU

Shannon Airport, 1950s modernity and a late modernist romance of the West in Elizabeth Bowen’s A World of Love (1955)

This paper challenges current views of 1950s Ireland as a troubled, isolated and culturally moribund state. It re-examines 1950s Ireland as a continuation of pre-war Irish modernism and home to cultural and literary experiment that gave birth to 1960s postmodernism. In fact Ireland was experiencing economic benefits from its special relationship with the US and from the Marshall Plan. Shannon Airport and the Shannon Development were central to post-war modernization.

Elizabeth Bowen is one of Ireland’s most experimental novelists; her first Irish novel The Last September (1929) focused on an Anglo-Irish big house and used modernist and realist techniques to interrogate the War of Independence in the light of Anglo-Irish and Irish-Nationalist cultural politics. This paper will explore her second Irish novel, A World of Love (1955) and its experimental representation of Ireland’s troubled yet positive transition from post-independence cultural-nationalism to post-war modernity and cultural exchange between Ireland and other countries, in particular America. By focusing on Bowen’s juxtaposition of a decaying Anglo-Irish big house and Shannon Airport and her switching between different narrative styles: romance; fairytale; realism; modernism and surrealism, it will re-examine the novel as a late modernist allegory of Ireland in the 1950s at a crossroads between the past and the post-war future.

Dr Anne Markey Trinity College Dublin

Modernism, Maunsel, and the Irish short story.

The relationship between revivalism and modernism is a complex one, not least because both terms are contentious and neither movement was unified. This vexed relationship can be seen in the short stories of Patrick Pearse (1879-1916). Advocating the use of vernacular Irish and the eschewal of traditional folk narrative templates, Pearse was a progressive theorist and practitioner who believed that modern Irish-language literature should reflect modern experience. No insular traditionalist, he insisted on the necessity of engagement with contemporary international literary models and maintained that the short story was the ideal modern literary form. Íosagán agus Sgéalta Eile, containing four short stories written by Pearse between 1905 and 1906, was published by the Gaelic League in 1907. An Mháthair agus sgéalta eile, containing six further stories written between 1907 and 1915, was published in 1916. Following Pearse’s execution, Maunsel and Co. published Joseph Campbell’s translations of all Pearse’s stories as part of the Collected Works of Padraic H. Pearse in 1917.

The stories in Íosagán agus Sgéalta Eile and those in James Joyce’s Dubliners were written during the same period. Connections between the two collections suggest a nuanced relationship between revivalism and the emergence of modernism that is complicated by the role of Maunsel and Co. in the publication history of Dubliners and the dissemination of Pearse’s short stories. While Pearse’s stories contained stylistic innovations that revolutionised the development of the Irish-language short story, their setting in an idealised Connemara Gaeltacht valorised the traditional over the modern. My paper will explore the interplay between modernity and tradition in these stories to suggest that revivalism and modernism in the Irish context can be seen as both complementary and antithetical responses to contemporary cultural conditions.

Dr Michael McAteer, Queen’s University Belfast

German Expressionism and Irish Drama: Yeats, O’Casey and McGuinness.

The influence of the German Expressionist movement on the Irish Dramatic Movement at the start of the 20th century is thought to be slight. Yeats’s rejection of O’Casey’s ‘The Silver Tassie’ appeared to embody a general antipathy at the Abbey Theatre to the style of Expressionism and the radical internationalist politics associated with it. This paper makes the case for the significant influence of Expressionism on Yeats’s drama, in the first instance through dramatists who were important predecessors for the movement, Frank Wedekind and August Strindberg, and later, through Ernst Toller, the most important playwright to emerge from Expressionism. The case is made here for re-evaluating Yeats’s relationship to O’Casey in the light of the shared influence of Toller in the 1930s. The paper examines parallels between Wedekind’s ‘Spring Awakening’ and Yeats’s ‘The Land of Heart’s Desire,’ the influence of Strindberg’s ‘The Ghost Sonata,’ Toller’s ‘Masses Man’ and Yeats’s ‘The Player Queen.’ The politics of O’Casey’s ‘The Silver Tassie’ is considered in the light of these influences, Yeats’s decision to stage the play at the Abbey in 1935 motivated by his encounter with Toller’s work. Finally, the enduring legacy of Expressionism in 20th century Irish drama is traced through Yeats and O’Casey to Frank McGuinness’s, ‘Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme.’ It is argued that the political ambivalence of this play has much to do with the controversy surrounding ‘The Sliver Tassie,’ pointing to the local pressures marking engagement with experimental forms in European theatre developed since the 1900s.

Jacqueline McCarrick NUI Maynooth

The Great Hunger, an apocalypse of Irish modernism and surrealism

Referring to The Great Hunger, Edna Longley states in Poetry in the Wars ‘the idea in the 1930s and 1940s that there “ought” to be a Modernist Irish poetry led to an overestimation of such poets as Denis Devlin and Brian Coffey. Meanwhile Kavanagh’s indigenous technical revolution – which involved digestion but not imitation of The Waste Land – remained under appreciated.’ My proposed paper (for the TCD symposium) does not set out to prove an ‘overestimation’ of the work of Devlin and Coffey, but to assert the revolutionary aspects of Kavanagh’s long poem and to establish his poetic as not at all antithetical to the work of the so called ‘European’ Irish poets of the 30s - Devlin, MacGreevy, Beckett and Coffey. My paper takes as a premise that between Britain and Ireland in this period there were at least two separate ‘casts’ of modernism developing simultaneously, and that Kavanagh and the Irish Europeans loosely ‘belonged’ to these two different camps. (Kavanagh looked primarily to the British ‘realist’ model of the Auden generation of poets.) As Alex Davis states in Broken Line: Denis Devlin and Irish Poetic Modernism

One can take a lead from [Billy] Mill’s speculation that because Ireland, with the exception of Belfast ‘missed out on the process known as the industrial revolution,’ its modernism is of a different cast (my Italics) from that of other first world countries.

The realism of The Great Hunger is in no doubt, but there is much evidence to suggest that Kavanagh’s Audenesque poem is much more than social document, consisting of a number of modernist procedures (other than realism) such as surrealism. My proposed paper examines these modernist procedures giving the surrealist aspects of the poem particular attention.

Bernadette McCarthy University College Cork

Painting Stories, Telling Pictures: W. B. Yeats and Word Image Ideologies

“I was bored to death by that routine, and in consequence I have left Art, and taken to Literature”.1 W.B. Yeats was reflecting on his training in visual art. However, this paper will argue that he never left art but developed a visual perspective in literary form. Elizabeth B. Loizeaux’s Yeats and the Visual Arts grounds Yeats’s early work in the practice of Pre-Raphaelite artists and charts a development from poem as picture to poem as sculpture. W.J.T. Mitchell’s Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology uncovers the ideological basis for interpretative strategies that divide image and word and at the same time promotes the adoption of interpretive procedures of ideological analysis “to reveal the blind spots in various texts” (4). My perspective denies the conventional view that upholds a word image dichotomy. Rather, in the context of Yeats’s literature, I see word and image as comparably expressive of visual ideas. This creates an opportunity not only to revisit his work from a new perspective but also to compare the visual forms created by Yeats in words to the visual forms created in graphic media by his contemporaries. I offer a re-evaluation of Yeats’s participation in what has come to be called visual culture, and a re-engagement with his work advancing the critical lens developed in word and image relation methodologies. This approach affords a new perspective on the relation and boundaries between visual and literary arts in national and international Modernism.

Dr Jenny McDonnell, Trinity College Dublin

‘The Brassy Little Shopgirl’: Frank O’Connor and the legacy of Katherine Mansfield

This paper aims to interrogate Frank O’Connor’s engagement with the work of Katherine Mansfield in his seminal study of the short story, The Lonely Voice (1962). O’Connor’s chapter on Mansfield is a conflicted one, simultaneously acknowledging her reputation as a ‘woman of brilliance, perhaps of genius’ and expressing distrust that this was offset by her professional and personal shortcomings as ‘a clever, spoiled, malicious woman’. Appearing nearly forty years after Mansfield’s death, The Lonely Voice would seem to rank alongside the most caustic mid-century backlashes against her after the publication of a series of posthumous hagiographies written and edited by her husband John Middleton Murry. O’Connor’s argument, however, is more noteworthy because of his problematic stance towards Mansfield as an exponent of his own preferred genre, and his discussion is underpinned by an implicit exclusion of Mansfield from the tradition of great short story writers that he constructs within The Lonely Voice. It will be suggested that this is indicative of the problems that Mansfield’s legacy posed for the generation of short story writers that followed her, a difficulty that was further heightened by questions of nationality. By comparing O’Connor’s response to Mansfield with that of the New Zealand short story writer Frank Sargeson, this paper will question the extent to which O’Connor’s feelings of uncertainty about the woman he termed ‘the brassy little shopgirl of literature who made herself into a great writer’ may fundamentally be attributed to an inherent mistrust of her modernist aesthetic in fiction and her seemingly cosmopolitan ideals.

Rhiannon Moss, Queen Mary, University of London

Thomas MacGreevy, Catholicism and Modernism in 1930s Ireland

Thomas MacGreevy has often been seen as a problematic figure in discussions of Irish modernism. His commitment to nationalism and Catholicism may seem difficult to reconcile with his engagement with international modernism. This paper will argue that the apparent irreconcilability of these attitudes is based on an overly simplistic division of Irish writing in the 1930s into modernist exiles and conservative nationalists. By examining MacGreevy’s criticism through the decade, in particular his attitude to TS Eliot, I will show MacGreevy attempting to define a kind of Catholic modernism capable of invigorating modern writing. His own poetry, in its development from and points of tension with Eliot’s influence, is an effort to shape this style in a national context and so create a distinctively Irish modernist form.

I will argue that rather than the imagined break in MacGreevy’s work marked by his return to Ireland in the second world war, his later criticism on Jack B Yeats is a consistent development from his earlier work. In his insistence there on the importance of national art combining both ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ tendencies, he is echoing arguments made in the Catholic press in Ireland on the nature of a modern national literature, which themselves are related to strands of Catholic social thought. MacGreevy’s importance is in his combination of these ideas with the principles of European literary movements, in particular Eugene Jolas’ transition manifestos, and his insistence on a narrative of Irish writing which is both international in outlook and determinedly Catholic and nationalist

Dr Eugene O’Brien, MIC Limerick

‘He Had Read Hour out a Ghost Story’: Hauntological Identifications between James Joyce’s ‘Eveline’ and Claire Keegan’s ‘The Parting Gift’

Jacques Derrida’s programmatic slogan ‘Il n’y a pas de hors-texte’ (there is nothing outside the text) can be rewritten, and indeed has been rewritten by him as ‘Il n’y a pas de hors contexte’ (there is nothing outside of context). This paper will engage with two key concerns of the conference: the re-examination of Irish modernist writers’ work in relation to their contemporaries and Claire Keegan’s postmodernist short story in light of the alteration of context from Joyce’s ‘Eveline’. Both stories deal with women as victims of both familial and social patriarchy, with different aspects of abuse, with the lack of communication within families, and with the need for escape from constricting circumstances. It is my contention that Joyce’s modernist story is hauntologically present in Keegan’s postmodern tale.

In James Joyce’s short story ‘Eveline’ from Dubliners, the protagonist is permeated by the sense of paralysis that permeates the entire collection. A responsibility to her violent father, accentuated buy the death of her mother some years previously, means that although she has the opportunity to begin a new life with her boyfriend in Buenos Aires, free of restrictions and open to new opportunities, at the last moment, she decides not to go, but doesn’t seem to know why this is so.

In Claire Keegan’s short story ‘The Parting Gift’, from Walk the Blue Fields, the central character is also bound by a sense of duty to her father. In this case though, the duty is much more overt and dysfunctional. She recalls how, after her mother ceased havng sex with her father, she was sent into her father’s room in her place. Like the father in Joyce’s sotry, he tries to obstruct her departure, in this case not by emotional or physical abuse, but by refusing to give her money. Although the story ends with her in a toilet cubicle of an airport, the reader is still not sure whether she will emigrate, and doubt is created through descriptions of her brother, who intends to move out of the family farm, but who, she feels, will spend his life working the same fields.

Stylistically ‘Eveline’ is hauntologically present in ‘The Parting Gift’ as each story is framed by images of stasis of the central character in the face of motion all around her. By comparison and contrast of these intertextually-related stories, this paper will examine whether a discernable shift is evident between the modernist and postmodernist contexts of Joyce and Keegan, respectively.

Eimear O’Connor, University College Dublin

Modernity and Realism: Sean Keating and The Playboy of the Western World

Universally, all aspects of the arts, including theatre, literature and the visual, are essential to the evaluation of the development of the modern world. The invention of photography can be included as primary to the encouragement and dissemination of innovative creativity. It is manifest that Irish artists in the early to mid- twentieth century were fully aware of the necessity to develop interdisciplinary approaches to their work, while at the same time, engaging with modern invention. The centenary of the first production of John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World is an excellent moment to introduce an aspect of Irish artist Seán Keating’s work that heretofore, has been to a large degree, overlooked. Therefore, this paper will examine the close association between the realism of The Playboy of the Western World, and Keating’s ten paintings commissioned for the illustrated de lux edition of the play, published in 1927, which now signal his early, but so far substantially unacknowledged connection with technical invention, with the modernity of self-location, and with the Abbey Theatre. The paper will also offer a new conceptualisation of the tension and discourse between ‘modern’ and ‘academic’ in the visual arts in the Irish post-colonial environment, which has arguably been too dependent on apparent binary oppositions that ultimately have encouraged a dependence on controversy and celebrity.

Dathalinn O’Dea, Boston College

Staging the Nation: W. B. Yeats and Theatre as the Third Space

Yeats criticism has been particularly attentive to the way in which the poet’s work embraced a type of nationalism that sought to romanticize and reinscribe Irish identity, to (re)interpret and (re)present Ireland’s colonial history in an attempt to invent a distinctly postcolonial Ireland. Such readings of Yeats’s poetry and drama have tended to privilege the former and to overlook both the subversive potential of theatre to critique and destabilize hegemonic power structures, and its role in articulating cultural and national identities. Similarly, modernist criticism often elides the features of Yeats’s work that belie his self-appointed position as the enemy of the movement; and the inclination to restrict literary modernism to the work of poets and novelists further obscures his plays from critical inquiry. My paper seeks to address the inherent political potential and resonance of Yeats’s drama, namely its discursive and historical relationships to imperialism and the ideologies that inform its production and reception. Moreover, it examines aesthetic strategies of subversion and resistance in light of modernist aesthetic experimentation and cultural disintegration, and attempts to map the experience of imperialism onto Yeats’s dramatic modernism. Interrogating and extending Rob Doggett’s reading of On Baile’s Strand (1904) as an attempt to dismantle Arnoldian “notion[s] of cultural incorporation”1 and related racial tropes, I will explore the issue of hybridity in the construction of culture and the Yeatsian stage as the Third Space. I hope to present Yeats’s theatre as a site of analysis, where postcolonial and modernist preoccupations find dramatic expression, and where culture and history intersect with performance and representation.

Dr Deaglán Ó’Donghaile, NUI Maynooth

Liam O’Flaherty and the Irish Revolutionary Bohemian

Liam O’Flaherty’s 1925 novel, The Informer, presents an alternative view of the formation of the Irish Free State. It was, in O’Flaherty’s words, a hardboiled urban thriller, written “more by instinct than by thought” and as he pointed out in his memoir, Shame the Devil, it also had an international influence, having been inspired by the German left-wing revolts of the early 1920s. This cultural and political context explains why the “glorious romance of the slums” and its anti-authoritarianism is valued by O’Flaherty’s bohemian characters:

The one glorious romance of the slums is the feeling of intense hatred against the oppressive hand of the law, which sometimes stretches out to strike some one, during a street row, during an industrial dispute, during a Nationalist uprising. It is a clarion call to all the spiritual emotion that finds no other means of expression in that sordid environment, neither in art, nor in industry, nor in commercial undertakings, nor in the more reasonable searchings for a religious understanding of the universal creation. (p.47)

O’Flaherty’s revolutionary community is not dissimilar to that constructed by Walter Benjamin for whom modernity appeared as an endless political conflict. For Benjamin, the modern city was “an ever-active hotbed of revolution” existing in a continual “state of emergency” which threatened to shatter tradition and displace “the traditional value of the cultural heritage”. Paying close attention to Benjamin’s theory of history as an endless dialectic of class conflict, this paper will argue that with its themes of political disorder and resistance to the state The Informer expresses a popular and especially politicized form of modernism.

Wit Pietrzak, University of Lodz

Predefining Modernism: W. B. Yeats and the Symbolic Ontology

It is perhaps the most salient feature of W. B. Yeats’s oeuvre that his poetic personal, ulike those of Eliot’s and Pound’s (Emig 62), seems to remain pronounced at all times and never falters. However, the uncertainty as regards the condition of the world and its ontological principles pervades his poetry in an equal measure to that of his contemporaries. According to Vereen Bell Yeats deals with the feeling of unrest by making “his art arrange the world about it in its own pattern” (Bell 76) so that “it can outstare history” (Bell 104). Since, in Nietzsche’s words “everything that sets man off from animals depends upon his capacity to dilute concrete metaphors into schema” (Nietzsche 250), Yeats’s lyrics will be analysed with a view to specifying his means to structure the schemata of his thought and through it the external milieu. I shall probe two aspects of the persona’s relation to the reality. On the one hand the imaginary Byzantium and its connection to the true world will come under focus; on the other various personals of Yeats’s poems will provide a basis for effectuating the link between the symbolic city and “the living stream”. The poet’s endeavour will thus reveal a new ontological ground on which the poet wished to erect his vision of the historical moment. That effort, in turn, will be posited as inherent in the modernist struggle with the ubiquitous feeling of disillusionment.

Professor Paige Reynolds, College of the Holy Cross

Colleen Modernism: Media and Materiality in Twentieth-Century Irish Women’s Writing

The innovative writing of Elizabeth Bowen is now enjoying a well-deserved moment in the literary critical spotlight. However, Irish modernist studies, such as it is, largely overlooks women writers. For instance, it ignores experimental writers like Brigid Brophy and Mary Manning, restricts Kate O’Brien to a dreary realism, and charges Dorothy Macardle with conformist historiography. Yet writers like these traveled in circles with influential modernists, and their work frequently corresponds with the formal and thematic characteristics of this literary movement.

In this paper, I will focus on the relationship of two Irish women writers to media culture and material culture, categories that currently inflect our understanding of international modernism. The lives of Elizabeth Bowen (1899-1973) and Mary Manning (1905-1999) spanned a century that saw the rise of mass culture, and each woman explored in her writing the influence of photography, film, radio, and television on daily life. As well, each critically examined the effects wrought by the proliferation of “things” in twentieth-century consumer culture. By comparing representations of media and materiality in their early and late work, I will argue that their engagement with these cultures can be explained in part by their itinerancy. Bowen lived most of her life in England, and Manning resided for long periods in America – but each regularly returned to Ireland for extended periods. This particular style of modernist exile, one characterized by the peripatetic rather than by exodus, helps to explain their perceptive use of media and material cultures in the form and content of their writing.

Dr Ellen Rowley, Trinity College Dublin

Dublin Architecture 1945- 1960: The Case of Catholic Church Design…

Architecture under the lens of Irish Studies: Culturally twentieth century Ireland has see-sawed somewhere between Europe and America and it has courted (in unequal measures) both introversion and Internationalism. The architecture arising out of such duality in turn bears witness to the abandonment of emigration and the fruits of diasporic contact alike. It is so intimately bound to the mis/fortunes of the State but unlike the heroic idiosyncrasies which for example mark Ireland’s literature, Irish architecture is not so formally definable or recognizable.

Experiment in Error: Irish Women Poets Engaging with Modernism in the 1930s, 40s and 50s:

In an essay on the Irish modernist poet Thomas MacGreevy, J. C. C.

Mays writes that “MacGreevy has a special place in the Irish tradition, because he was a modernist, but he was a special kind of modernist because he was Irish.” An essay in the same collection, by Anne Fogarty, mentions the “almost forgotten names” of some Irish women poets writing around the same time as MacGreevy, noting that, while the special situation of Irish male modernist poets often consigned them to an obscurity from which their work is only recently being recovered, their female colleagues’ work has endured an even greater degree of segregation from the accepted literary canon. “To triumphantly reinstate their work by seeing it as part of a diffuse but coherent literary context which embraces male and female writing alike,” states Fogarty, “would involve a self-blinkering and premature denial of the unremittingly androcentric and fragmented nature of the Irish modernist literary scene.”

This paper will explore the work of those of MacGreevy’s contemporaries whose careers have been filtered through that other layer of “specialness” – their gender. As Mays points out, falling between two (or three) stools can catalyse the production of more original and challenging work, and Irish women poets who became excluded from the dominant nationalist tradition and grappled with the (arguably similarly exclusive) innovations of European modernism could bring their difference to bear on the emerging themes and forms which they encountered. The beautiful, highly innovative poetry which resulted can, I believe, no longer be discounted by scholars of Irish modernist literature.

Dr Eibhlín Evans, University College Dublin

"'a lacuna in the palimpsest'; A Reading of Flann O'Brien's At Swim Two Birds."

This paper will offer a reading of Flann O’ Brien’s novel, At Swim Two Birds (1939) as an insightful and innovative engagement with issues of Irish identity and Irish literary culture. Literary criticism has celebrated O’Brien’s novel, applauding its comic inclinations, its deconstructionist strategies, its post-structural affinities, its anarchic tendencies, its multi-generic inclusions and its Joycean range of literary styles and voices. However, none of these critiques give a satisfactory explanation for the structural originality of the text nor do they explain the exclusively Irish orbit of O’Brien’s novel.

This reading of At Swim Two Birds identifies it as ‘a lacuna in the palimpsest’ of Irish identity formation in which the author’s anarchic tendencies are central to his assault on a particular ideology, on the literary vehicles employed in its promotion, and the impact on Irish writing that such a situation produced. I will argue that this novel can be read as a disruptive intervention in the layering of literary proscriptions for Irish identities which preceded its publication in 1939. O’Brien’s literary strategies can be understood as deliberate attempts to escape the strait-jacket of an identity model contained within a range of nationalistic narratives, employed and promoted as desirable in Ireland for half a century.

We can recognize this novel as a literary challenge to a particular cultural agenda where O’Brien’s literary strategies and his varied inclusions combine in a sophisticated assault on the real repressions, and the often comic absurdities, involved in a particular situation, that is, the repressive cultural nationalism of Ireland in the 1930’s and its impact on Irish writing and on Irish identity. O’ Brien’s novel takes the prevailing narrative models and, through their playful juxtaposition, he offers a serious critique of the limiting and confining imperatives behind their endorsement and their employment.

Professor Lisa Fluet, Boston College

James Joyce, Scholarship Boys and British Cultural Studies

This paper presents the beginnings of a reception-history of Joyce’s major works, within the context of the literary histories of literature in English emerging through British cultural studies. Focusing principally on the critical work of H. G. Wells, George Orwell, Raymond Williams, Richard Hoggart, and Paul Gilroy, I am interested in developing an account of the return to a postimperial “English” culture exemplified by the turn to cultural studies in the postwar period, and anticipated in the early critical work of Wells and Orwell. Following Jed Esty’s recent study A Shrinking Island, this paper traces the development of “James Joyce” as a disciplinary object for literary criticism, and the various ways in which Joyce has been deployed as an exemplum of cosmopolitan, anti-nationalist modernism (Moretti and others), as well as an exemplum of a nationally-specific Irish modernism (Nolan, Duffy) and “semicoloniality” (Howes, Attridge). Joyce as a subject for British cultural studies has posed some interesting difficulties: Williams’ Leavisite tendencies, for example, and the ways that cultural studies came to be interwoven with British political life and the New Left in the post-war period, have led to a de-emphasis of Joyce within cultural studies’ histories of the specifically English novel. This situation leads me to Paul Gilroy’s work, specifically, and the ways in which he has analyzed the collusion between British cultural studies and keeping the “black out of the union jack.” At the same time, this paper focuses on the fate of a social type identified in Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy—the “scholarship boy”—within Joyce’s works. Taking up Stephen Hero (1904), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), and Ulysses (1922), I reconceive Stephen Dedalus’ difficulties in maintaining social poise in terms of literary modernism’s ambiguous novelistic relations with the figure of the awkward, earnest and anxious “scholarship boy.” Working backwards from Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy (1957), where the scholarship boy’s difficulties with sociability were first most famously treated, I analyze the complications posed to Hoggart’s study—and to its post-war participation in defining both culture and society as objects of study—by the figure of the modernist, Irish scholarship boy.

Dr Eamonn Hughes, Queens University Belfast

Flann O’Brien, Modernism and Popular Culture

Considerations of Flann O’Brien’s status as modernist or post-modernist writer, as of his relationship to James Joyce’s work, have focused to a large extent on the formal and ludic aspects of his writing. Remembering that O’Brien was part of a student generation in the 1930s ‘equally concerned’ as his contemporary Niall Sheridan put it, ‘about the cultural identity of the new State and its place in the wider intellectual context of Europe…’ enables us to think about the ways in which his texts, particularly At Swim-Two-Birds and the ‘Cruiskeen Lawn’ column, engage with European aesthetic and cultural debates, particularly in regard to ideas about tradition and, in turn, about the ownership and control of culture. By reference to two key essays on tradition and history - T. S. Eliot’s ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ (1919) and Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936) - this paper will make the case that O’Brien’s writing constructs an idea of tradition which is more accommodating of popular culture than either High Modernism, arguably constructed as a bulwark against the burgeoning of mass culture, or the Irish Free State which was still anxious about how such matters should be evaluated and policed.

Dr Benjamin Keatinge, South Eastern European University, Macedonia

Coffey, Devlin, MacGreevy and the Poetry of Prayer

“All poetry” wrote Samuel Beckett in his 1934 review of Thomas MacGreevy’s Poems “is prayer”. This insight might serve as a unifying principle underscoring the Catholic modernism of Coffey, Devlin and MacGreevy. Whether it be Devlin’s overt religiosity in such poems as ‘Est Prodest’ and ‘The Heavenly Foreigner’, or MacGreevy’s “humanistic quietism”, or Coffey’s meditative questing in such poems as Advent and ‘The Prayers’, all these poets use prayer, and intercession, as part of the method, rhetoric and content of their poems. J.C.C. Mays describes Brian Coffey’s poetry as a “poetry of intention”, rather than revelation and fulfilment and it is this aspirational quality which unifies these poets’ work. They are, in Beckett’s words, waiting “for the thing to happen” and it is implied that “the meaning is in the waiting” (R.S. Thomas, ‘Kneeling’). This paper explores the solipsistic and communicative function of prayer in these poets’ work finding that their “pure winged linking” (‘Est Prodest’) involves, in Brian Coffey’s terms “acts of recognition of an adult humility based on hope.” These Catholic aesthetics both overlap with and resist the nationalistic pieties of 1930s Ireland in a complex relationship with Irish social reality which this paper also addresses.

Dr Róisín Kennedy National Gallery of Ireland

The White Stag Group – Experimentalism or Mere Chaos?

The cultural isolation of the war years had a dramatic impact on the exhibition of contemporary visual art in Dublin. The period saw growing public awareness of modernist art. This increased interest was partly the result of an influx of foreign artists into Dublin, the most significant of which was the White Stag Group. Founded in London in 1935 by Basil Rákóczi and Kenneth Hall, the group reformed itself in Dublin in 1940. Other artists gravitated towards the group, and participated in its exhibitions, held between April 1940 and October 1945.

This paper will examine the critical debate on modernist art in Ireland generated by the exhibitions and associated publications of the White Stag Group. These presented Irish critics with a number of difficulties. The theoretical underpinning of its art practice was new to an Irish audience, who were unaccustomed to art which claimed to be solely concerned with personal expression. As a result the White Stag prompted a more complex critical response than that found in relation to other manifestations of modernism in Irish visual art. The cosmopolitan approach of the White Stag challenged conventional expectations of art as reflective of communal and, by extension, national principles. This paper will examine how the self-promotion and determination to connect its work to the international art world made the White Stag an important precedent for later developments in Irish visual art.

Dr Sean Kennedy, St Mary’s University, Halifax

Ireland/Europe…Beckett/Beckett

This paper will explore ways in which a more nuanced account of Irish modernism can resolve a recurrent tension in Beckett Studies between two entities, ‘the Irish Beckett’ and ‘Beckett the European’. Often, there is an implicit either/or logic that structures debates about Beckett’s Irishness, suggesting that Irishness and modernism are somehow mutually exclusive categories of experience, so that Beckett only truly becomes modernist when Ireland ‘disappears’ from his work after 1946. Tracing the persistence of that binary in the critical work of Vivian Mercier, Richard Kearney and, more recently, Stan Gontarski and Chris Ackerley’s Grove Companion to Samuel Beckett (2004), I want to challenge the notion of Ireland as an impediment to modernist experimentation, and explore ways in which Irishness has, in fact, been an extraordinarily fertile source of modernists sensibilities, paying particular attention to Beckett’s post-war work. In a close reading of Gontarski and Ackerley’s introduction, and drawing on recent theoretical work by Terence Brown, Joe Cleary, Adrian Frazier and others, this paper will suggest the need for a re-evaluation of Ireland’s relationship to modernism and, by the same token, of Samuel Beckett’s relationship to both. The aim is to deconstruct the Ireland/Europe binary and refute certain too-easy assumptions about Ireland’s status as a place and mentalité to be escaped in the quest for artistic freedom.

Dr Edwina Keown, St Patrick's College, DCU

Shannon Airport, 1950s modernity and a late modernist romance of the West in Elizabeth Bowen’s A World of Love (1955)

This paper challenges current views of 1950s Ireland as a troubled, isolated and culturally moribund state. It re-examines 1950s Ireland as a continuation of pre-war Irish modernism and home to cultural and literary experiment that gave birth to 1960s postmodernism. In fact Ireland was experiencing economic benefits from its special relationship with the US and from the Marshall Plan. Shannon Airport and the Shannon Development were central to post-war modernization.